What are the agreements that music creators typically enter into with business partners, clients and licensees?

Please note: The information provided on this site does not, and is not intended to, constitute legal advice. Instead, all information, content, and materials available on this site are for general informational purposes only. Be sure to consult with a legal expert before signing any agreement. (See where Canadian music creators can seek free or affordable legal counsel.)

For professional music creators, ironing out agreements with partners, clients, licensees, and others is par for the course. And though the language may seem confusing and the negotiation process daunting, getting deals in writing is absolutely vital to ensuring that creators are legally protected. (Unfortunately, while verbal agreements and handshakes do constitute valid legal contracts, proving what they were and entailed can be a challenge in a court of law.)

While each contract often contains a large number of unique variables, there are really only a few standard types of agreements that music creators will encounter on a regular basis. These include publishing agreements, production contracts/composer agreements, synchronization agreements, and commission contracts, and it’s advantageous to understand the purpose of each and what they typically comprise.

Publishing Agreements

If a creator chooses to partner with a music publisher, their relationship will be formalized by way of a publishing agreement, and usually one of two types—a co-publishing agreement or an administration agreement. These differ in a number of key ways, which impact the scope of the relationship between the partners.

Co-publishing Agreements

Over the last few decades, co-publishing agreements have become the industry standard, and they typically entail the following:

- The music creator assigns to the publisher part of the copyright (usually 25%) in a musical work or works written during a stated period (typically three to five years). An “exclusive” agreement covers all the works written by the creator, while a “non-exclusive” deal pertains only to specific works—and sometimes just one.

- A percentage of the royalty revenue is also allotted to the publisher—typically half of the customary publisher’s share, which is 25% of all royalties (the creator will receive 75%, which comprises the full writer’s share and the other half of the publisher’s share).

- In turn, the publisher agrees to administer the copyright and find ways for the works to be used, with some restrictions outlined by the creator (e.g., the works aren’t to be played at political rallies or in ads for alcoholic beverages).

- In addition to administration, the publisher usually invests in the creator’s career development and artistic output.

- The publisher may also cover certain expenses or give the music creator an advance that’s recoupable against future earnings. Learn more about advances from music publishers.

- The length of the partnership—or the “term of agreement”—can vary, but the initial commitment is usually for three to five years, with the publisher reserving the option to extend that commitment a set number of times.

- The length of the publisher’s partial copyright ownership—or the “term of assignment”—is usually the full life of the copyright, although some publishers may be willing to accept a shorter term. This, however, is all subject to negotiation.

This is called a “co-publishing agreement” because the music creator retains partial ownership of the copyright in their works, which technically makes them a publisher as well. And, clearly, if a work is co-written by multiple creators, they each own a part of it and can only sign away the portion that’s rightfully theirs.

And while the points above outline the most common elements of a co-publishing deal, there can be many variations. For example, the term of the agreement may be based on a specified number of songs or albums to be written rather than a length of time. And the scope may include the creator’s existing catalogue in addition to future works.

Before this type of deal became standard, “full publishing agreements” were the most common. They involve the creator assigning full ownership of the copyright (which is why they’re also called “buyout agreements”) and allotting the entire publisher’s share—that is, 50% of all royalties—to the publisher. Today, full publishing deals are relatively rare, partly because there are more avenues of self-promotion available to creators than ever before, and because there’s a greater impetus to retain at least partial ownership of their intellectual property.

Administration Agreements

When a music creator doesn’t wish to give up any portion of the copyright in their works, but needs assistance with licensing and royalty collection, they may sign an administration agreement with a publisher. This type of deal differs from a co-publishing deal in the following key ways:

- The publisher’s role is limited to administering the copyright in the music creator’s works. Creative services are less likely to be offered.

- In exchange, the creator will pay the publisher a percentage of the net income derived from the works (usually 5–15%), but full ownership of the copyright remains with the creator.

- No advance is typically given to the creator.

- The term of the agreement is usually two or three years.

Creators aren’t the only industry players to sign administration deals. Production companies that own the musical works used in their films, TV shows, video games, or other properties often enter into these agreements with publishers as well.

Sub-publishing agreements are also common, but they don’t involve music creators. They’re signed when a publisher engages another publisher (or “sub-publisher”) in a foreign territory to promote music and collect royalties directly from collective societies in that locale. For example, if a music publisher in Quebec thinks some of their songs might be of interest to licensees in France, but they don’t have a strong footing there, they’ll sign a sub-publishing deal with a French publisher who has an established relationship with those licensees and SACEM, France’s collective society for music creators and publishers.

The term of a sub-publishing agreement is typically 3–5 years, and the sub-publishers are given a portion of the publishing royalties accrued in their territory as compensation (usually 5–10%). The remaining revenue is then remitted by the sub-publisher to the publisher to be split with the music creator based on the agreement they entered into with each other.

Production Contracts/Composer Agreements

When an original score is required for a TV show, movie, video game, or other audiovisual (AV) production, the production company will engage a music creator to create one. The deal they establish in the production contract/composer agreement typically takes the form of either an assignment deal or a licence deal.

The Screen Composers Guild of Canada (SCGC) believes that:

1) Ownership and control of publishing and copyright of musical work should remain with its creator(s), and:

2) A synchronization and master use license for the use of a musical work in an audiovisual project is sufficient to allow the producer to exploit the project.

At the same time, SCGC is cognizant that certain audiovisual producers take the position that they require a grant of rights in a screen composer’s work as a condition of engagement.

While SCGC believes there is no legal or moral basis for such a coercive position, SCGC is aware that it may be difficult for emerging composers to prevail on this point of negotiation, particularly where the producer positions this point as a “deal breaker.”

Assignment Deals

Assignment deals are more commonly adopted for higher budget productions, and they usually entail the following:

- The music creator, clearly defined as an independent contractor and not an employee of the client, agrees to write (and usually record and deliver) original music for use in the AV production and, potentially, ads, trailers and/or other related promotional content.

- They also agree to a grant of rights in which they assign full or partial ownership of the copyright in the musical work (and the sound recording, if applicable) to the production company.

- Notwithstanding the grant of rights, the creator typically reserves certain associated rights and revenue participations in the score:

- Where the creator agrees to assign 100% of the copyright in the score (i.e., compositions and sound recordings) to a production company, they should ensure that they retain performing rights, which will allow them to receive their writer’s share of performance royalties. Indeed, if they’re a member of SOCAN, Canada’s performing rights organization (PRO), they’ve already assigned these rights to SOCAN and therefore cannot assign them to any other party.

- Where the creator retains partial ownership of the copyright, then they also retain an interest in the publishing rights of the work (a subset of copyright) and should ensure that they negotiate participation in the publisher’s share of performance royalties (in addition to receiving the full writer’s share).

- Further, if they agree to produce the sound recording and perform on it, the creator should reserve neighbouring rights, which will allow them to receive the performer’s share and negotiate a percentage of the maker’s share of neighbouring rights royalties.

- The parties may also agree to split reproduction rights royalties including mechanical royalties and/or revenue from sheet-music sales, soundtrack sales, or other sources.

- The creator will likely waive their moral right to the integrity of the work as well, but should aim to reserve their right of attribution. In fact, the contract should outline exactly how the creator will be credited (e.g., what text will accompany their name, where their credit will appear in relation to the others, how prominently it will be displayed, etc.).

- In exchange for all of this, the client will pay the creator an upfront fee, which may be intended to cover the creation of the musical work only or, more commonly, the production of a sound recording as well (including, where applicable, the hiring of musicians, the booking of studio time, and any other resources). Learn more about fees for custom music used in AV productions.

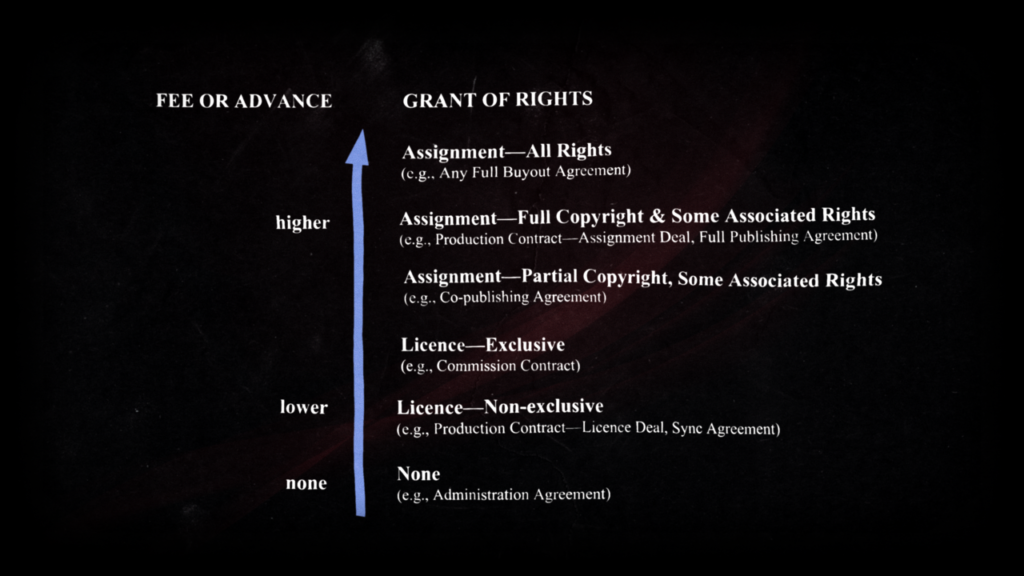

- Generally, the more rights a creator agrees to give up, the higher the fee they should require. And in the case of streaming productions, creators may wish to negotiate significantly higher upfront compensation to account for the minimal back-end revenue they can expect to receive compared to the royalties derived from traditional media (e.g., broadcast TV).

- The composer’s fee is usually broken into a number of scheduled payments, beginning, for example, with the commencement of work or finalization of the deal memo and ending with the delivery of the sound recording and any other necessary materials to the client.

- A number of other logistical details will be outlined in the contract as well, including key deliverables and due dates; the required delivery format of the master recording (e.g., as a Pro Tools session) and other technical specifications; stipulations regarding the scope of changes the client can make to the music before finalization; clarity around the production company’s responsibility to complete and submit the cue sheet to the creator’s PRO, etc.

Please note that any deal requiring a music creator to assign the entire copyright in their work to a client in exchange for a one-time fee and no additional compensation (including any royalties) is what’s commonly referred to as a “full copyright buyout.” Read more about buyouts and their implications.

Full buyout agreements often contain “work for hire” language, but since copyright law in Canada does not recognize the US “work for hire” provision, music creators can contest its inclusion in Canadian contracts. It should be noted, however, that just because a “work for hire” clause is included, doesn’t necessarily mean that the agreement constitutes a full buyout. If the contract also says that the creator has the right to collect the writer’s share of royalties, then it’s actually a “limited copyright buyout agreement.” And if the creator is willing to accept it, then they may decide that it’s not worth seeking the removal of the “work for hire” clause.

License Deals

The licence deal is the go-to form of composer agreement and much preferred to the assignment deal, which it differs from in the following key ways:

- The creator still agrees to write (and usually record and deliver) original music for a production. However, they retain full ownership of the copyright in the musical work (and the sound recording, if applicable) as well as all associated rights, and grant the production company only the non-exclusive right to use their work, in defined territories and for a defined term, in the ways outlined in the contract—and only those ways.

- They may negotiate to keep all the revenue generated from the use of their work, or they may instead choose to share certain revenue streams with the client.

- The creator reserves their moral right of attribution, while retaining the right to the integrity of the work may be more negotiable.

- Because the work has the potential to generate substantial back-end revenue for the creator—and they’ll be able to pursue additional ways to exploit their intellectual property—the client may seek to negotiate a lower upfront fee, essentially paying them only for the time they spend writing (and, if applicable, producing, engineering, performing, editing, and mixing) the work, rather than for the acquisition of the copyright in it. Learn more about fees for custom music used in AV productions.

Synchronization Agreements

When a production company or other licensee wants to include all or part of a pre-existing musical work in their project, they’ll negotiate a synchronization (or “sync”) agreement with the owner or administrator of the copyright in the work—which is usually a music publisher or a self-published creator. (Importantly, if the licensee wants to use a specific sound recording in their production, they’ll also need to negotiate and obtain a master-use licence from the owner of the recording.) Sync agreements typically entail the following:

- The publisher or creator grants the licensee a non-exclusive right to synchronize the musical work with the production and otherwise use it in the ways outlined in the contract—and only those ways.

- There is no assignment of any portion of the copyright in the work or associated rights. The publisher and creator retain the division of ownership established in their publishing agreement, if applicable.

- The creator will likely waive their moral right to the integrity of the work, but reserve their right of attribution (the publisher can’t waive moral rights because, under Canadian law, the creator is the only one who can possess them). And since a work may be edited to fit the context of an AV production, the creator may request approval rights to ensure that its integrity is maintained.

- In exchange for all of this, the licensee will pay the publisher or creator an upfront sync fee. Learn more about fees for pre-existing music used in AV productions.

- The contract will also outline the scope of the use of the musical work, which comprises the following details:

- The term of the agreement (e.g., one year, a few years, in perpetuity, etc.), and, if applicable, any options to renew the licence when the original term expires

- The types of media the work will be synchronized with (e.g., free and basic cable TV; internet; all media, which would include theatrical, if applicable, etc.)

- How the work will be used in that media (e.g., as theme, background, featured, or logo music)

- The territories and markets where the media will be broadcast, streamed, or sold (e.g., Canada only, the US and Canada, worldwide, etc.)

- The types of promotional content the work will be used in (e.g. an “in-context” trailer for the production named in the agreement and/or an “out-of-context” use for a trailer to promote the film).

Generally, if the licensee is seeking a broad scope of use, the publisher and/or creator will seek to negotiate a higher sync fee.

- Some logistical details will be established in the agreement as well, including clarity around the production company’s responsibility to complete and submit a cue sheet to the publisher’s or creator’s PRO.

Though sync licences should almost always be non-exclusive, making it possible for the same musical work to be used by different licensees—and to generate revenue from multiple sources—simultaneously, in the context of advertising, a brand may want exclusivity for a limited time and in a particular product category. If the publisher or creator is willing to agree to this, they are likely to demand a larger upfront fee.

For most productions that are likely to be released in physical form (e.g., films or TV shows on Blu-ray disc), the sync agreement may also include a one-time “home video” buyout fee, which is often included in the sync fee.

Where video games are concerned, the sync fee may be inclusive of the physical-media buyout; however, in many cases, the publisher or creator can negotiate a per-unit fee up to a specified number of units sold. And because gaming technology is constantly evolving, many sync licences granted to the larger production companies are perpetuity agreements, and the scope may include “future or new unknown platforms.” This means that the licensee won’t need to renegotiate the licence if their game has a longer shelf life than expected or is adapted to a platform that has yet to be invented.

Because pre-existing music is used in a wide variety of media, which are changing rapidly, it can be difficult for music creators to know if their work is receiving a fair remuneration in a sync agreement. This is one area where partnering with a music publisher can be advantageous. It’s part of their job to understand each media market and to negotiate the best sync fee possible with each licensee.

Read a sample sync agreement provided by the SCGC, annotated with explanatory notes.

Did You Get the Deal Memo?

Since contracts often contain many provisions outlined in minute detail, they can be lengthy and take a fair amount of time for the parties to iron out. And because AV productions are completed on tight timelines—especially TV shows—the process of writing and securing the music for these projects often needs to begin before the full contract is concluded.

In such instances, deal memos are signed to provide both parties with some assurances. These shorter documents outline the key points of the agreement—like the music creator’s fee, the payment schedule, the grant (and reservation) of rights, and the division of royalties and other back-end revenue—and note that the parties are committed to establishing a comprehensive agreement at a later date that will be negotiated in good faith.

When the deal concerns the creation of custom music, the production company may provide the creator with the first instalment of their fee as soon as they begin writing. However, it’s also common for clients to withhold any payment until a long-form contract is signed. This presents a degree of risk for the music creator, since there’s a possibility that they may end up disagreeing with one of the provisions in the full agreement, which could result in extended negotiations (and additional payment delays) or the deal falling through altogether. Fortunately, due to their timing and budget constraints, it’s also in the production company’s best interest for these agreements to be resolved.]

Read sample deal memos, annotated with explanatory notes. (To access the files, download the folder, open the “Reference Files Annotated” subfolder, and select “ANNOTD 03a” and “ANNOTD 03b”.

Commission Contracts

When an individual or a music-based arts organization like a symphony orchestra, chamber ensemble, or choir wishes to support a music creator, expand a performance repertoire, pay tribute to someone, or mark a special occasion, they may commission a composer to write an original musical work to be performed live. And this agreement is formalized via a commission contract, which usually encompasses the following:

- The composer agrees to write a musical work of an approximate duration and a particular instrumentation (dictated by the size and type of the ensemble), and deliver a performance score to the commissioner. It is typically the commissioner’s responsibility to copy the parts in the score, which the composer reserves the right to review and approve.

- In exchange, the composer will receive a commission fee according to a payment schedule outlined in the contract (e.g., 50% on signing the contract, 10% on delivery of the score, and the rest at agreed-upon intervals between these two events). Learn more about commissioning fees.

- Full ownership of the copyright remains with the composer, and they don’t usually assign, license, or waive any of their associated rights (although the commissioner must purchase a performance licence from the composer’s PRO, which is SOCAN in Canada).

- The commissioner is granted the exclusive option to perform the musical work within a defined time period. If they wish to extend this period for any reason, they may do so for a fee noted in the agreement.

- The composer reserves the right to attend rehearsals of the work, and they agree to take part in workshops or reading sessions for an additional fee. They’re also expected to help publicize the performance of the work by taking part in interviews or making other appearances, with their expenses covered by the commissioner.

- Additional details outlined in the contract will include:

- How the composer should be credited in promotional materials and the concert program

- How the commissioner should be acknowledged when other ensembles perform the work

- How many complimentary tickets the composer will receive for the premiere

- Who will be responsible for the composer’s travel expenses and accommodation (usually the commissioner)

- Whether the performance will be recorded in anyway, and how the recording will be used (e.g., for archival purposes or to promote a future performance)

If the composer performs a service or assumes a role that’s outside the scope of what a music creator normally does (e.g., conduct the performance of their work or act as a performer), a separate agreement is typically established to address this. An additional contract is also required if a record label wants to produce and release a recording of the live performance of the work.

It should be noted that the contract details and sample above are specific to purely musical productions. When music is commissioned for a dramatic production like a musical, opera, or ballet, the music creator’s copyright is essentially bundled together with those of the other creative contributors (e.g. choreographers) under the umbrella of “grand rights.” And the related agreement—including all front- and back-end compensation—needs to be negotiated with the presenter or producer. Visit the Canadian League of Composers website for more information on grand rights.